Why the “I’m HSP” Label Isn’t Enough: A Professional’s Take on the True Nature of Sensitivity

Have you ever felt a wave of relief after realizing, “Maybe I’m an HSP (Highly Sensitive Person)”?

For many, discovering the concept of HSP provides a much-needed language to validate their lifelong experiences. At the same time, however, a growing number of people find themselves quietly struggling: “Even after trying various HSP-specific coping strategies, the fundamental difficulty in my life hasn’t changed.”

In clinical settings, we often find that behind what is described as “sensitivity,” there are factors that cannot be fully explained by HSP alone. In many cases, these factors involve stress and trauma that have been overlooked precisely because they are woven into the fabric of what we call “ordinary daily life.”

In this article, as a Certified Public Psychologist, I will explore the true causes of persistent distress hidden behind the HSP boom, drawing on the latest clinical insights.

1. The HSP Boom and the Shadow It Casts

Over the past several years, the term HSP (Highly Sensitive Person) has rapidly permeated society. Bookstores are filled with titles about “sensitive people,” and the concept is a staple of media and social networks. Using HSP as a way to explain one’s difficulties has become increasingly common.

In counseling settings, more clients now describe themselves using terms like, “I think I’m HSP,” or “I seem to fit the HSS-type HSP.” This language can serve a vital function by allowing people to understand their struggles without falling into self-blame.

However, specialists have raised significant concerns (notably developmental psychologist Shuhei Iimura; see Questioning the Merits and Pitfalls of the HSP Boom, Iwanami Booklet). The concern is that the concept of HSP has become diluted and detached from its academic definition, often being treated as a “catch-all” explanation for every form of psychological distress. While it is a specific trait, it is currently being burdened with excessive meaning.

Originally, HSP refers to Sensory Processing Sensitivity (SPS)—a trait describing individual differences in how one responds to sensory stimuli. It is neither a medical diagnosis nor a pathological condition. It does not inherently explain the cause of psychological dysfunction, nor does it automatically imply special talent or superiority.

Furthermore, sensory processing sensitivity exists on a continuum; there is no clear line separating “HSP” from “non-HSP.” Popular classifications like “XX-type HSP” lack academic evidence. When these nuances are lost, the concept risks being exploited by commercial interests or applied in extreme, misleading contexts.

The core issue is that over-relying on the HSP label may inadvertently divert attention away from the root causes that truly need to be addressed. In clinical practice, while I deeply respect each client’s narrative, I often find that “HSP” alone provides an insufficient explanation for their pain.

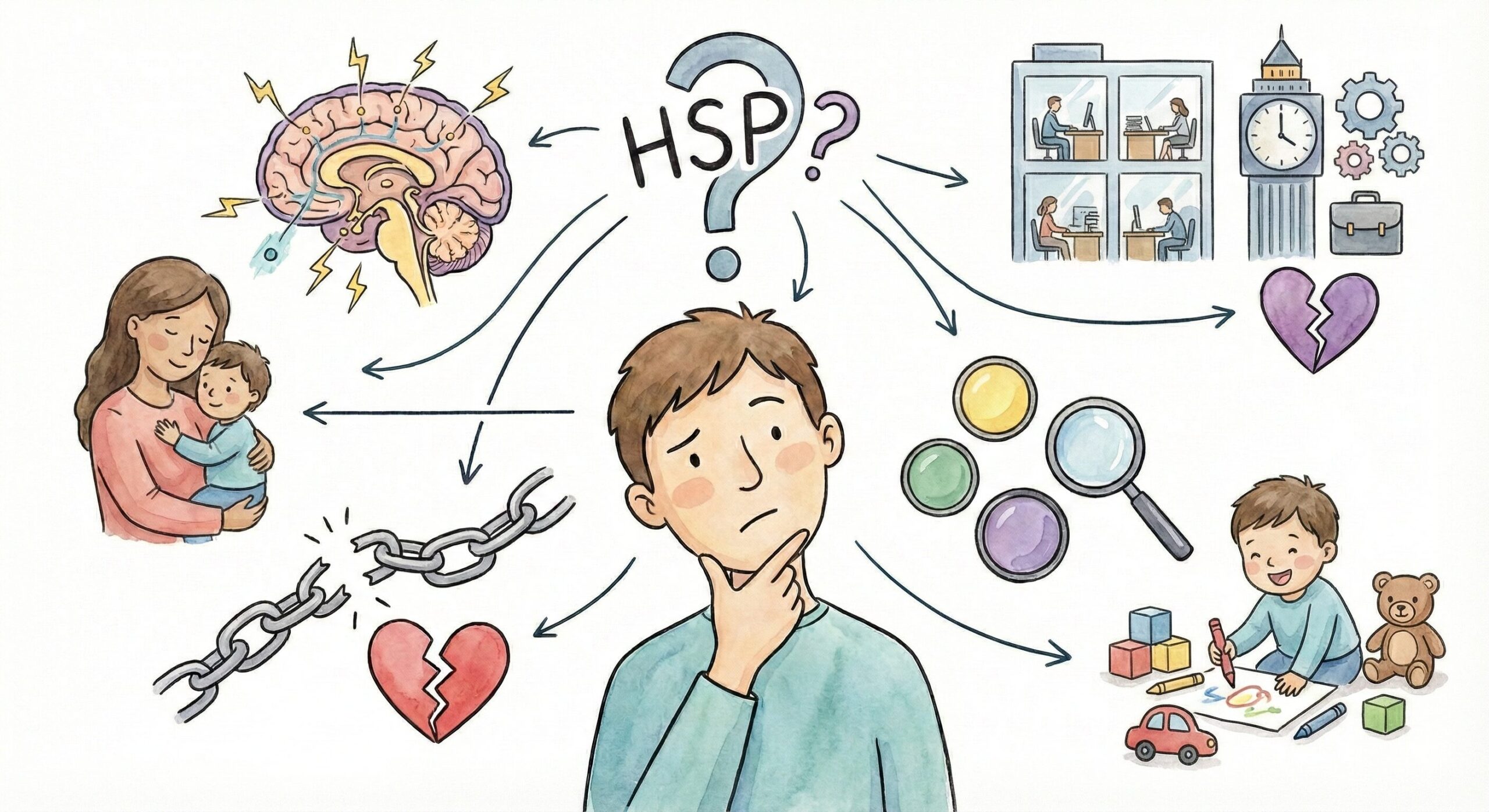

2. Where Does “Sensitivity” Come From? The Need for a Multifactorial Perspective

Sensitivity, hyper-reactivity, and a chronic sense of difficulty in living do not arise from a single source. Many characteristics labeled as “HSP” actually stem from diverse backgrounds.

For instance, sensory hypersensitivity (or hyposensitivity) is a well-known feature of neurodevelopmental conditions (such as Autism or ADHD). In other cases, early environment shapes how a person regulates interpersonal distance, leading to chronic tension in relationships. Conditions such as depression, anxiety disorders, and OCD can also manifest as heightened or blunted sensitivity.

Additionally, prolonged stress can exhaust the nervous system, impairing the body’s ability to regulate sensory input. Chronically tense environments—whether at work or at home—are significant burdens in themselves. Cultural expectations, social pressure, and economic status also play major roles.

As clinical psychologists and psychiatrists, our role is to carefully integrate these multiple factors. A psychological concept should not be a label for pigeonholing someone, but a “working hypothesis” to support their recovery and self-understanding. When HSP is treated as the sole explanation, we risk repeating historical mistakes where other labels were over-applied, leading only to further confusion.

3. Developmental Stress: The Overlooked Root of Distress

In recent years, research has renewed our focus on the impact of stress experienced during childhood and adolescence as a primary background for adult distress.

Events that appear minor to an adult can place an overwhelming burden on a developing child. For example, repeated marital conflict—even without direct physical violence—significantly affects a child’s brain development and emotional regulation. This is now recognized as a serious issue known as “exposure to domestic violence.”

Excessive stress during these formative years has been studied through the lens of Developmental Trauma and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). Large-scale studies show that individuals with high ACE scores face significantly higher risks of mental health struggles and physical illnesses in adulthood.

Similarly, attachment research shows that early relationships with caregivers have long-term effects on self-esteem and interpersonal health (often discussed as “Attachment Disorders”). Crucially, symptoms caused by developmental trauma often closely resemble neurodevelopmental traits. As a result, environmental influences are frequently misattributed to innate biology.

4. Trauma Is Not Just About “Extraordinary Events”

We often associate the word “trauma” with catastrophic events like disasters, accidents, or violent crimes. However, clinical reality shows that trauma frequently stems from far more ordinary, everyday contexts.

Even without a single dramatic incident, inescapable stress sustained over long periods reliably reshapes the mind and body. Humans are particularly vulnerable to chronic, low-level stress.

In this sense, trauma can be reframed as a “stress disorder born from the accumulation of everyday strains.” Power harassment, moral harassment, bullying, chronic family tension, and subtle failures in caregiving all leave deep marks—often without the individual realizing it.

The results—chronic hyper-vigilance, excessive adaptation (people-pleasing), interpersonal difficulties, and anxiety—are the body’s way of surviving. So-called “sensitivity” is often a manifestation of this survival state.

From this perspective, modern mental health care is shifting toward an approach that first assumes the presence of trauma when seeking to understand distress. The difficulties we have been labeling as “HSP” need to be re-examined within this broader, more accurate context.